2025 GFA Lecture Notes

Exploring African Diasporic Classical Guitar Music

Lecture Abstract:

Black music and music from other diverse cultures deserve preservation and recognition equal to their Eurocentric counterparts. To truly understand the classical guitar, we must comprehend its complete history, which spans the globe. Composers like Brouwer (Cuba), Villa-Lobos (Brazil), Takemitsu (Japan), and Bogdanović (Yugoslavia) provide some insight into the guitar’s diverse origins. However, until recently, many cultural traditions and musical contributions to our instrument have remained unrecognized.

This lecture, which introduces Damian Goggans’ research on AfroClassical Guitar music, aims to highlight the contributions of Black composers to the classical guitar tradition. It will discuss the connectedness of Black classical guitar music throughout the diaspora and invite audiences to analyze this musical soundscape. One that has been shaped by resilience, innovation, and global exchange. Through performances and analyses of works such as Petro from Franz Casseus’ Haitian Suite and Jesus, Won’t You Come By and By from Thomas Flippin’s 14 Etudes on the Music of Black Americans, audiences will deepen their understanding of the musical structures, cultural contexts, and interpretive questions essential to this repertoire.

———————————————————————————————————

—Link to Google Slides—

———————————————————————————————————

Good afternoon, everyone! My name is Damian Goggans, and I am truly honored to stand before you today!

—

For those of you who may not know, I am a classical guitarist, composer, actor, and music researcher. In May of this year, I earned my Bachelor of Music in Classical Guitar Performance from Oberlin Conservatory. There, I studied under the mentorship of Stephen Aron. I also completed a Minor in African American Music, guided by Dr. Courtney Savali-Andrews.

I started playing guitar in 2016 through an after-school program with Brian Gaudino, who at the time was the Director of Education for the Cleveland Classical Guitar Society. Then, during high school, at the Cleveland School of the Arts, I was one of two inaugural students in the Musical Pathway Fellowship at the Cleveland Institute of Music. Through that program, I got to work closely with Erik Mann and Lisa Whitfield, and had a handful of lessons with Colin Davin and Jason Vieaux. In 2020, I was one of 14 in the inaugural class of the GFA mentorship program, where I worked with Chris Mallet and Raphaël Feuillâtre.

Since beginning to play guitar, I’ve had lessons with the likes of Thomas Flippin, Pepe Romero, Adam Holzman, Matt Cochran, and Bill Kanengiser. And this fall, I will get to continue my guitar studies at Oklahoma City University with Matt Denman and the Leyenda Foundation.

—

Before getting into my lecture, I’d like to teach you a really important rhythm that may show up later.

—(Teach Rhythm)—

—

It is my hope that in doing this lecture here today, I can encourage more conversations on classical guitar music from overlooked communities and cultures. Ones that focus on the history and performance practices associated with said repertoire.

I will start by providing some background on my research. Then I will introduce some books, scholars, and authors whose ideals I’ve grounded my research in. I will then end by discussing how all of this shows up in Thomas Flippin’s 14 Etudes on the Music of Black Americans.

—

During my time at Oberlin, I began the research that I’m sharing with you today—on music by composers of African descent, which I will refer to as “AfroClassical Guitar Music”. This project is one that is both academic and personal.

Recently, in my life as a musician, I became acutely aware of the lack of cultural representation in my repertoire. At the start of this project, I was only made aware of three Black classical guitar composers: Justin Holland, Celso Machado, and Thomas Flippin. But I knew there had to be more composers whose identities, like mine, reflect the African diaspora.

Expectedly, I was right; their contributions had simply been overlooked until recently.

—

Thus, I’ve committed myself to uncovering and uplifting the contributions of my people throughout the diaspora, especially in relation to the guitar. My research and performances are my offering to help fill this gap in the canon. To honor my ancestors. To contribute to the guitar’s complete global history. And to show those who come after me, wondering if Black people play the classical guitar, that they belong.

—

My research started with an anthology of classical guitar music by Black Composers and arrangers. This ever-evolving list, which now has about 65 composers, was published in the Music Library Association’s Notes Quarterly Journal. You’ll see a link to this at the end of my talk.

—(Explain Slide)—

As can be seen in the slide, for each entry, I have: Composer, Name of their work, instrumentation, and info on purchasing their scores.

Eventually, I want to continue expanding this list and make it easily accessible for anyone who wants to learn more about this music.

—

Along with this anthology, I intend to gradually put together a database that has biographies, recordings, and scores of all of the music written by these composers. This process has already been started as I’ve made a website and social media pages dedicated to housing my research.

The other half of my research involves examining how AfroClassical Guitar music connects to other Black musical styles across the diaspora.

—

It is important to note that my research is in no way the first of its kind. I am preceded by the work of various guitarists, scholars, and organizations, including:

Christopher Mallett and Ernie Jackson’s research on Justin Holland

Dr. Ciyadh Wells and Neil Beckman’s Directory of Guitar Music by Black Composers(it’s important to note that Dr. Wells has also done a considerable amount of research on classical guitar music by Black women composers.)

Changing the Canon by Ex-Aequo

AfroClassical by Aitua Igeleke

The GFA Spotlight Series

The Cleveland Classical Guitar Society’s Composers-in-Residence Program

—SECTION: Foundational Scholars and Literature

—

Before getting to the focus of today’s talk, there are a handful of things I believe one should consider when approaching AfroClassical Guitar music.

First and foremost is the understanding that Black music, throughout the diaspora, is more than a collection of organized sounds and complex rhythms. Our music holds our histories. It is a cultural database. An archive. It is a language that heals, honors our ancestors, and makes room for the future. As an extension, our instruments serve as a vehicle for articulating our lived experiences.

To explore this further, I’ve turned to a range of sources:

Africanisms in African American Music by Portia K Maultsby

The Healing Wisdom of Africa by Malidoma Patrice Some

What Makes That Black? by LUANA

Signifyin(g) Within African American Classical Music by Christopher Jenkins

—

The first one is a paper titled, Africanisms in African American Music. Here, the esteemed ethnomusicologist Portia K. Maultsby explores the connectedness of Black American music to its African Diasporic roots. She argues that Black music cannot be fully understood by simply identifying rhythms, scales, or instrumentation.

Instead, it is the process—the dynamic, communal, and adaptive nature of the music—that defines its essence. In these traditions, there is usually an understanding that what you play or sing is not nearly as important as how and why you do it.

Dr. Maultsby highlights this by quoting J.H. Kwabena Nketia, a Ghanaian Ethnomusicologist and Composer, who says that: “African-derived music must be studied as an evolving creative process-one that connects us to our cultural identity, even in the absence of traditional instruments.” In other words, Black music exists not just as a sound, but as a lived experience that is rooted in history and charged with meaning. And the aforementioned process is what connects this music across the diaspora.

—

So, what is this creative process? Ethnomusicologist Dr. Mellonee Burnim offers three key aspects of Black music making:

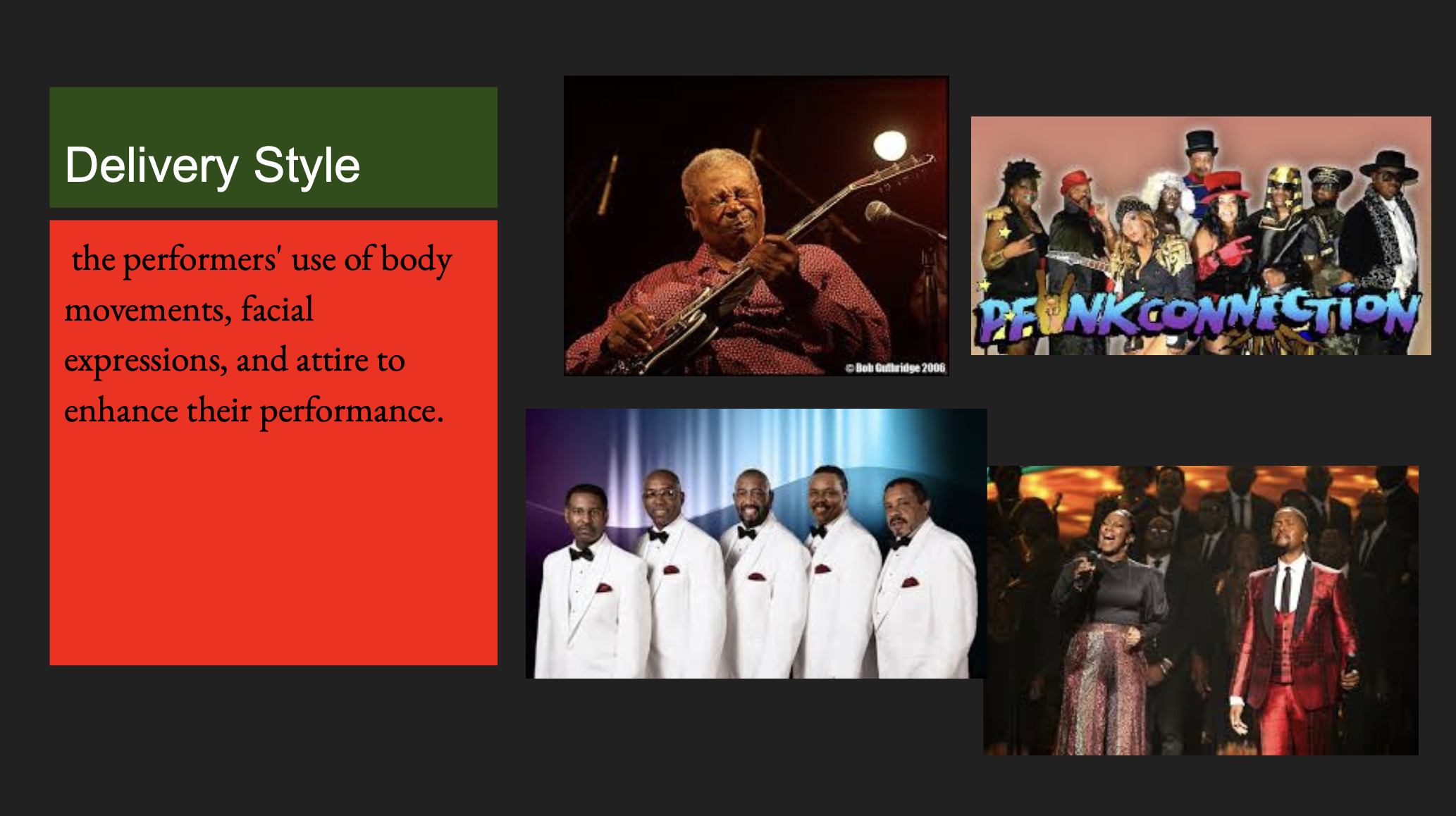

Delivery style encompasses the performers' use of body movements, facial expressions, and attire to enhance their performance.

ex. Think of a gospel singer bending back to get a note. The elaborate costumes or suits worn by artists like George Clinton, Michael Jackson, and The Temptations. Or the facial expressions guitarists like BB King make while soloing.

(NS)Sound quality, which prioritizes the translation of everyday experiences into living sound.

This includes vocal and instrumental techniques that evoke emotion or mimic human expression, such as the use of “blue notes”, a musician making their instrument “cry” during a solo, or a gospel singer, who has been overtaken by the spirit, yelling out their song at the height of their performance. A great example of this is Jimi Hendrix’s performance of the Star Spangled Banner at the 1967 Woodstock Festival.

The mechanics of delivery highlight the unique character and interpretation that each performer brings to their musical expression.

Think of jazz standards like Autumn Leaves, All the Things You Are, or Fly Me to the Moon. There are many recordings of the songs, none of which sound exactly the same. Each artist reshapes the melody, reharmonizes the chords, or stretches the rhythm in a way that fits their own voice.

—

In my research, I also came across a book titled: What Makes That Black? : The African American Aesthetic in American Expressive Culture by LUANA. The author starts by articulating points that are quite similar to the other ethnomusicologists I’ve mentioned thus far.

She then goes on to discuss numerous core concepts that structure Black performance traditions. There are three in particular that I believe are most beneficial to today’s talk.

Aesthetic of the cool: “This personal and artistic style expresses the eminence of royalty, stillness, composure, and down-to-earth elegance with a touch of flamboyance and audacity.”

Examples include a performer singing or playing an instrument with effortless mastery, projecting a confident sense of self, or entering a room with poise and presence—“as if they own the place.” Think of how people like Nina Simone, Prince, Ma Rainey, or James Baldwin carry themselves. This aesthetic is not only visual or performative, but deeply tied to cultural resilience and dignity.

Blues- pain into art: This is the act of transforming personal pain, difficulty, and struggle into music, song, poem, dance, painting, rap, sculpture, story, theatre, or conceptual art.

Think of the song Strange Fruit by Billie Holiday, which was a protest song against lynchings. Or Maya Angelou’s poem The Mask, which discusses how Black people hide their pain and struggle daily to be more palatable to society.

Call and Response: This concept is extremely important as it makes room for communal engagement.

This is present in various forms of Black culture and music. In live performance, for example, when James Brown shouts “Hit me!” and his band instantly responds with a tight rhythmic interjection—that’s call and response. In the Black church, when a preacher asks, “Can I get an amen?” or says, “Turn to your neighbor and say…”—that’s call and response. It’s not just a musical technique—it’s a way of building community.

—

There’s also an important concept known as signifying. According to Christopher Jenkins, in his article Signifying in African American Classical Music:

“Signifying is a complex practice, functioning as a mode of indirect and coded communication that conveys multiple meanings specific to particular cultural groups with specialized knowledge.”

Even though this usually shows up verbally—through jokes, stories, or metaphors—it can also happen through music, especially in styles like jazz, blues, and gospel. For example, a musician might play a version of a familiar melody but twist it or change it in a way that says something deeper. I once again offer Jimi Hendrix’s version of the National Anthem as an example of this. It’s not just a performance, it's a layered protest, a sonic critique of American hypocrisy during the Vietnam War and Civil Rights era.

Signifying only works if the listener knows the original reference or is part of the community that understands what's really being said. It’s less about what’s being played or said on the surface and more about the hidden message underneath that connects people through shared knowledge and culture.

In the context of AfroClassical Guitar repertoire, signifyin’ occurs when a composer embeds their work with cultural or historical subtext. This may manifest through conscious quotation of a spiritual or folk melody, the use of rhythmic structures associated with African or diasporic traditions, or the evocation of communal memory—such as grief, struggle, or triumph—through musical gesture.

—

As I have listened to and analyzed works within AfroClassical guitar repertoire, one theme has continually surfaced: much of this music seems to function as a form of ritual.

In my own performances and practice sessions with this music, I’ve found myself in a state that I at one point referred to as being “connected or plugged into the universe.”

There’s a particular scene in Ryan Couglar’s film, Sinners, that I’d like to play for you, which perfectly depicts what I feel is happening in such moments.

—(play clip from I Lied to You)—

Just like Sammy in this scene, I become engulfed in the music and performance. In those moments, the only things that seem to be in existence are me, my ancestors, and the stories we are co-creating.

—

I wanted to explore this experience more. So, I looked at the work of Malidoma Patrice Somé, a Dagara elder and scholar of West African spirituality. In his book, The Healing Wisdom of Africa, he says:

“Every time a gathering of people, under the protection of the spirit, triggers a body of emotional energy aimed at bringing them very tightly together, a ritual of one type or another is in effect” (Somé, p. 142).

By this definition, ritual is not limited to traditional religious or cultural ceremonies—it is an emotional and/or spiritual experience. And anyone, regardless of race, religion, or cultural background, can be spiritually and/or emotionally affected by music.

In the context of AfroClassical Guitar performance, the audience becomes more than passive spectators; they assume the role of a congregation. The performer, in turn, steps into the position of a Black Preacher or West African Griot. They act as a conduit between the material and the spiritual, the living and the ancestral, the seen and the unseen. This dynamic turns the concert hall into a sacred space of transmission and transformation.

Somé further outlines four components that characterize ritual practice:

Preparation: setting the space, grounding intention, and signaling the start

Invocation: “a form of prayer that formally invites the spirit, or any kind of personal deity, to join and participate in what is about to happen” (p. 152).

Healing: the emotional or spiritual realignment that occurs through the ritual process.

Closing: “an expression of gratitude for what the presence of the Spirit has allowed to happen” (p. 157).

I would argue that this process is present in some way or another throughout the AfroClassical Guitar canon and will discuss this further in my musical analysis.

—

This brings us to the piece I would like to examine, 14 Etudes on the Music of Black Americans by Thomas Flippin.

In 2021, as a part of their Composers-in-Residence Program, the Cleveland Classical Guitar Society commissioned Thomas Flippin to write this set of student pieces. I was blessed to have been a part of the premier performance of this work, where I got to perform XII. Don’t Be Weary, Traveler and XIII. Wake Up, Jacob.

To promote the piece, Flippin recorded a video explaining his intention behind the work. Therein, he discussed wanting to explore the melodic context of Negro Spirituals. He also mentions the importance of this project as it relates to his ancestors. He is a descendant of enslaved African-Americans from Georgia and Tennessee and says that he “wanted to do justice to this music.”

In preparation for this composition, He went through over 500 melodies, and in reflection, he says:

“There’s so much beauty in [the spirituals]. Such rhythmic inventiveness, such complexity in terms of the phrase structure. The lyrics are incredibly profound. And then you realize this is some of the most popular and enduring folk music that humans have ever produced.”

Flippin notes how other popular instruments, such as the piano, already use these melodies in their standard repertoire and method books. But when it comes to the classical guitar, we have yet to fully engage with this tradition. In fact, there are only three other works that I’m aware of, which use the spirituals in a manner similar to what Flippin suggests: Guitarra by Ulysses Kay, Connie Sheu’s arrangement of Troubled Water by Margaret Bonds, or Jorge Caballerero’s solo guitar arrangement of New World Symphony by Antonín Dvořák.

As he states in the video, he hopes that “ people of goodwill, of all racial backgrounds, all geographies… rich, poor, black, or white can enjoy and connect with this music on a human level to empathize with it… [he hopes] that we can find the beauty [in this music]and share it with the world.”

In the past few years, I got to work closely with Thomas on these pieces. We’ve had numerous conversations and lessons on the etudes, especially in preparation for my premier recording of all 14 etudes, which was also commissioned by CCGS.

When I first began working on this music, I turned to the performance notes. There, Flippin says:

“It is important to remain mindful that these are sacred melodies sung by a people who had collectively been kidnapped, physically abused, sold away from their children, impoverished, banned from education, hunted, lynched, and tortured—for centuries. As such, a somber demeanor should be adopted when performing.”

These are not mere musical exercises. They are spiritual artifacts. Echoes of resilience and survival. Flippin calls the performer to approach them with reverence, not virtuosity for its own sake. He also suggests we read the lyrics aloud, share the original melodies with our audience, and root our performance in the context of the suffering and the joy that birthed this music.

I personally felt that the best way to ground my audience in this was to sing these melodies in the way they would’ve been originally presented, which Flippin has told me he enjoyed so much that he started to incorporate singing into his own performances. As I prepared to record this music, I felt it was even more important to speak about the history behind each piece to give our audience a deeper entry point into their emotional and cultural weight.

Further into the preface, Flippin also raises critical questions of representation, appropriation, and intent. Who has the right to perform these pieces? How can they be interpreted without exploiting their origin? In his words, “there will always be a constructive tension between representation and appropriation in the arts.” But for Flippin, the greater danger lies in silence. In allowing this music to remain obscured, while dominant cultural traditions continue to shape student repertoire unchallenged.

Before continuing, I’d like to play a recording of one of the etudes. Think of how everything I’ve said up to this point may be present in this video.

—(play Rise, Shine, for Thy Light is A-coming)—

—

At the end of the video, I gave some background on the piece. But as is the case with most artistic works in the African diaspora, there's so much more happening beneath the surface—musically, culturally, and spiritually. As I continue to mention, Black music is an ever-evolving archive of Black culture, and Thomas’ 14 Etudes provide a great example of this. I highlight this in my recordings of the Etudes.

In the etude that I showed you, Rise, Shine, for thy light is a-coming, I begin by signifying on a rhythm and practices found in African diasporic cultures.

One of which is the ring shout.

—(play Jubilee performed McIntosh County Shouters)—

The group I just showed you is called the McIntosh County Shouters. According to their biography,

“[They] are the principal, and one of the last, active practitioners of…the 'ring shout.’ The ring shout, associated with burial rituals in West Africa, persisted among African slaves and was perpetuated after emancipation in African American communities, where the fundamental counterclockwise movement used in religious ceremonies integrated Christian themes, expressed often in the form of spirituals. (National Endowment for The Arts)”

During a performance, which can be found in the Library of Congress, the Narrator for the McIntosh shouters, Bettye J. Ector says:

“Shouting refers to the dance-like movement of the participants. There were religious rules against dancing, which prohibited shouters from raising their feet off the floor or from crossing one foot over the other. [The shouters] move in a shuffling fashion characteristic of a holy dance. They often stoop over and move their arms to pantomime the song in a fashion reminiscent of African customs.”

The shouters usually move in a circle, and there's repetitive call-and-response between the song leader and the shouters. This cyclic repetition, which can be found throughout African-derived music, ties into a concept, which I cannot discuss further at the moment, called the Bakongo Cosmogram.

There’s one particular rhythm in the ring shout that stands out. (Clap rhythm) This can also be found in a practice known as Pattin’ Juba and Hambone, which I encourage you to look up should you be interested. Here are two examples.

—(Show examples and clap rhythm)—

Most of us may know this pattern of 3+3+2 to be the tresillo pattern or to be associated with the tango and other Latin musical traditions. But in my courses at Oberlin in Black music and dance, I’ve come to understand this through a different lens.

One of my mentors, Dr. Thomas Talawa Prestø (Artistic Director of Tabanka Dance Ensemble), a prominent practitioner of African Diasporic dance, calls this and other associated rhythms the “Agricultural Rhythmic Complex”. These rhythms emerged from the fields, the communal rituals, and the daily lives of Black peoples throughout the diaspora. These rhythms represent our ancestors. They connect us to the land, to the body, and to the collective memory of those who came before us.

—

Earlier, I mentioned that rituals were present throughout AfroClassical Guitar music, and this is certainly true in Flippin’s Etudes.

While the entire set of etudes can be grouped into the 4 stages of ritual(preparation, invocation, healing, closing). A form of ritual can also be seen in my videos of the etudes. Think about the one that I showed you. I start by singing the spiritual. I do this to prepare my audience and myself to imagine the world from which this music is derived.

Then I present my interpretation of Flippin’s étude. Allowing the ancestors and composer to speak through the music.

I follow this with a “sermonette”, speaking in a manner similar to a Baptist preacher or West African griot. This is my interpretation of the history behind the work.

Here I am directly referencing cultural wounds and offering dignity and hope in light of past, present, and future struggles.

I leave the closing of these particular rituals up to my audience.

The entirety of this work and the musical traditions referenced in Thomas Flippin’s 14 Etudes offer a lens into the way Black people have turned their pain into art, survival into celebration, and memory into music.

___

Before I close, I want to leave you with this:

This work doesn’t end with me, Thomas Flippin, Chris Mallett, Earnie Jackson, Aitua Igeleke, or Dr. Ciyadh Wells. It doesn’t end with organizations, like CCGS, GFA, or Ex-Aequo. It also doesn’t end with Black music.

I encourage all of you to engage with the stories, sounds, and traditions of communities that have long been underrepresented in classical music. Whether you’re a performer, scholar, educator, or student, there is space for you to help expand the diversity, depth, and humanity in our field.